Reimagining data and AI – Symposium panel

Researchers discuss potential futures of AI in regulation, literature and creative practice

The third panel of the UTS Humanising AI Futures Symposium held on 28 July – Reimagining data and AI – discussed the different ways AI is represented and understood in regulation, literature and creative practice. Dr Andrew Burrell from the School of Design (Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building or FDAB) chaired the session, which heard from UTS scholars Dr Suneel Jethani (School of Communication, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences or FASS), Dr Michael Falk (FASS), and Monica Monin and Dr Sara Oscar (School of Design, FDAB).

Introducing the final panel, chair Dr Andrew Burrell noted that researchers are “entangled in these complex networked systems in such a way that while it is possible to critique the systems, it is not possible to operate fully outside of them”. “Approaches to AI that centre imaginative thinking and creative practice offer ways forward, where agency in the conversation about the future is reclaimed. In doing so, it is possible to find ways of making visible the entangled networks involved in creating these systems, including ensuring appropriate means of attribution and transparency when it comes to the human and more-than-human data, which is currently hidden. In reimagining AI for a future worth wanting, each academic discipline has an important role to play – in taking a direct role in deciding how we will take back agency in shaping the future development of these technologies,” he said.

Dr Suneel Jethani spoke on the topic, ‘Does AI need a Hippocratic oath?’ “The short answer is no,” he said, adding that the question has been discussed and researched by UTS students in The Ethics of Data and AI class he teaches. “In the discourse about ethical AI, there have been calls for developers of AI to swear to ‘do no harm’ in the same way that medical doctors do. But this is a simplistic solution to a complex problem. Such an oath would obfuscate systemic drivers of risk and harm, ignore important relations within socio-technical systems, and relegate moral responsibility to individuals,” he said.

Describing the risk profile of AI systems, Jethani said it captures “organisational risk such as commercial losses and biased system performance, as well as reputational risk and loss of trust due to illegal, harmful or negligent treatment of consumers, employees, infrastructures and the environment”. The risk profile also encapsulates the consequences of regulatory breaches such as fines or prosecution, as well as broader societal, epistemological and existential forms of risk.

“Autonomous agents create new forms of human-computer interaction, and human-computer insurrection,” Jethani said. Displaying an image of the fatal crash of a Tesla vehicle on Autopilot mode in California in 2018, he said: “The gentleman who lost his life in this crash was a software engineer for Apple, a migrant worker from Harbin, China, working in the US. This type of scenario shows us many things that are wrong with the way we think about ethics and the assignment of moral responsibility. It also shows us that there are particular segments in society such as tech workers that are particularly sensitive to having different types of thresholds and tolerances for the risks involved in such systems.” Jethani outlined several other examples that force us to think about deeply about the complexities of ethical AI.

“It’s difficult to cultivate or enforce ethical practices in the deployment of AI technology because there are complex relations between stakeholders, and the barriers to making and using AI are low in terms of the resources and skills required to stand up and implement AI systems. Given this context, I argue that a Hippocratic-type oath won’t work for three key reasons. Firstly, there are significant differences between the ways that medicine and data science are professionalised. Secondly, it presents an individualised solution to a structural problem. Thirdly, the challenge of knowing if a harm exists in the present and anticipating harms in the future look very different in different areas of practice.

“Beyond this, the Hippocratic oath is transactional in nature, based on a duty of care that’s predicated on an asymmetrical one-to-one relation between doctor and patient. The Hippocratic oath doesn’t readily accommodate the role that patients play in their own care, or consider external agents such as a virus. We haven’t yet seen the full range of AI harms, though we’re seeing lots of warning signs – so rather than approaches to ethics that are predicated on harm we should look towards a ‘precautionary principle’.”

Jethani argued that rather than trying to make the AI profession responsible, we should explore “a combined top-down, bottom-up, and hybrid assignment of moral responsibility – especially models that might accommodate human-machine/human-data interaction”. He highlighted questions for researchers to consider: “Would a Hippocratic oath displace existing modes of collective activism? And how might a more appropriate ethics get baked into cultures of accountability within contexts where risky AI is being developed and deployed without being evacuated back to institutionally convenient norms?” See research by Jethani and others on this topic from [2022] and [2023].

Dr Michael Falk presented ‘The body of the machine: Old ideas about the future of physical AI’. “I'll start by putting the phrase ‘artificial intelligence’ or ‘AI’ in scare quotes,” he said. “The term was created in the 1950s by software engineers, and was used as a regulative concept to try to guide their research on what to do with this new invention, the digital programmable computer. They thought, this thing embodies logic, the rules of thought – maybe we could make it intelligent. But since that time, instead of being used as a regulative concept, ‘AI’ has become something that we label existing systems with – even though we know full well that none of them are intelligent.

“If we challenge the ‘AI’ term in this way, and start thinking about other artificial cognitive concepts, what other possibilities arise? And what new risks come into view? What would artificial wisdom be? What would artificial humility be? Artificial stupidity? What are these things? To delve into this, let’s look at the past speculations about artificial agents and what it might be like to live with them.”

Falk noted that he is a literary scholar of the 18th century. “So when I seek answers to questions, I just go and ask dead authors what they thought back then,” he quipped. He outlined several examples from literature from the 16th to 18th centuries of artificial or robotic elements, including “a robotic sidekick” in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene and a “large language model” in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels.

Describing what he calls the “Frankenstein syndrome”, Falk said: “If you frame the problem as one of artificial intelligence, then the problem always seems to be that these intelligent agents we’ve built will misbehave. And therefore, they need to be restrained with proper rules and guidelines and obligations. That’s the problem if you think there are things like Frankenstein – but that’s not what these systems are like at all. There is no system today that remotely resembles Frankenstein.

“I’m putting this rather simply to illustrate that this is not normally the way these things are discussed in our society. We’re still trapped in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, or in the nightmare of Mary Shelley, thinking that a large server rack is going to come out of the basement and take our jobs and poison the water. When ChatGPT says to you, ‘I am a generative model, and I can’t do that’, it’s a lie. There is no ‘I’ behind that. It’s not referring to anything, it’s just pretend. When the CEO of OpenAI appears before the US Senate and says, ‘Oh, we must be restrained, because we’re building these terribly intelligent beings that are going to rise up and destroy us all’, it’s marketing spin.” See more of Falk’s research on this topic here.

Monica Monin and Dr Sara Oscar spoke on ‘The role of creative practice in encountering and critically understanding AI’. Along with panel chair Dr Andrew Burrell, they are members of the Critical Visualisation Research Group in the School of Design. Monin noted that, “With the turn to generative AI, we have seen large language models and text-to-image diffusion models become even more accessible and deployed in diverse contexts through platforms such as Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and ChatGPT.

“Our encounters here are all about a ‘generativity’ as a relay or a technical step from one action or command to the next output. As an encounter, generative AI platforms seek to curtail, optimise and smooth out the activity of computational and other processes involved. To do this, it draws on a raft of resources, technical operations and human labour to manage and keep it seemingly on-task. To get large generative models to work at scale requires patching together all kinds of ways to make the raw materials such as datasets workable to this expansion.”

Monin observed that anthropologists have found that projects that strive towards scalability leave ruins through how they try to achieve scale. “One example of this is LAION (large-scale artificial intelligence open network). It collates massive datasets including five billion images through Common Crawl. But in order to create datasets that are used by platforms such as Stable Diffusion, it uses technical operations such as an aesthetic image prediction model, as well as processes of detoxification of content by human labor.” The “algorithmic imaginary we are being offered, as described by Tania Bucher [2015], is largely technocratic – knowledge generation is a technical problem that just requires the right ingredients”.

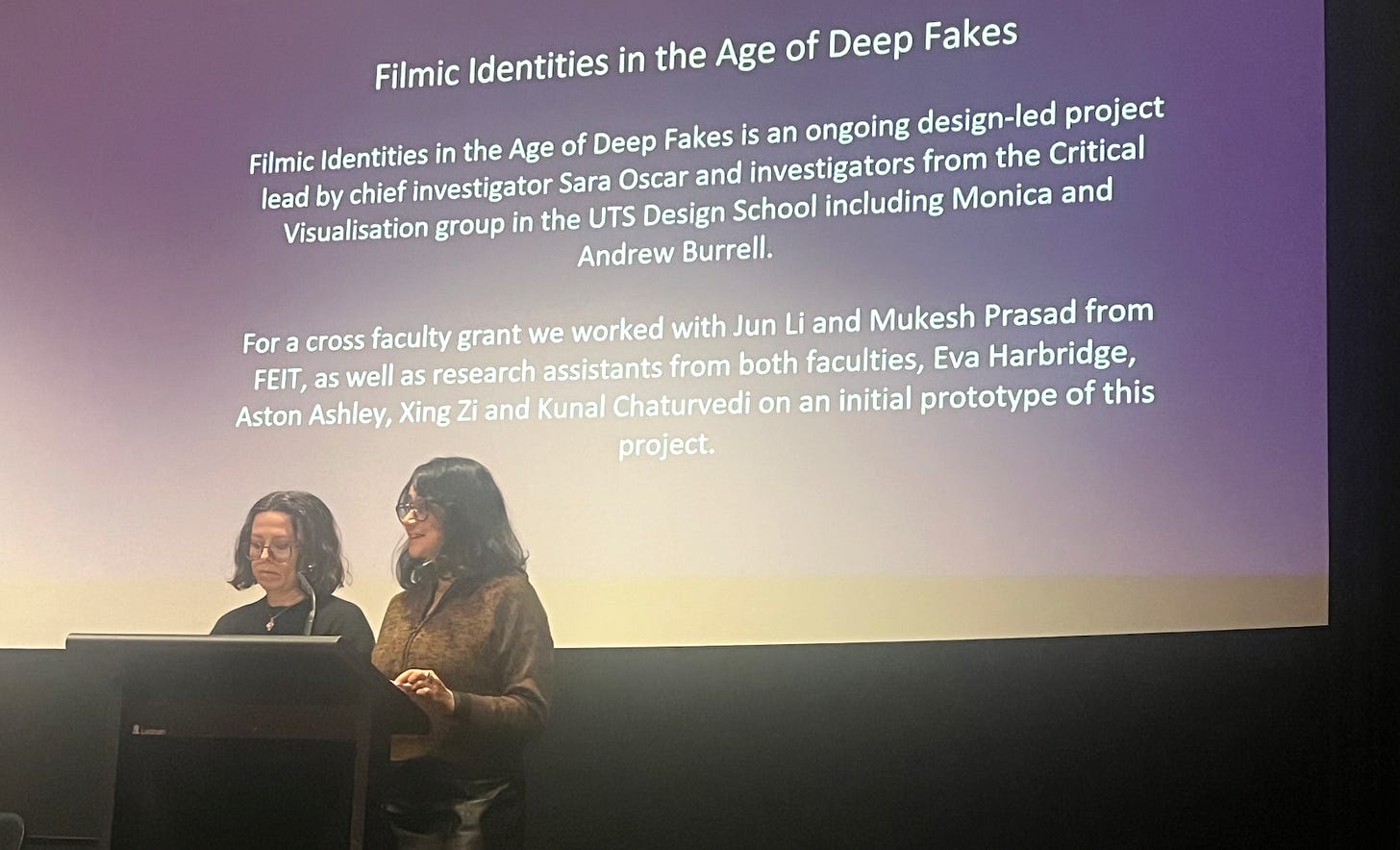

Dr Sara Oscar discussed their creative practice research project, ‘Filmic Identities in the Age of Deep-Fakes’. “We suggest that creative practice can open up other imaginaries and encounters with AI technologies, by enabling material engagement with them in ways that allow us to grapple with their ontology, beyond input and output interfaces,” Oscar said. “The Critical Visualisation Research Group in the School of Design is working on a project called ‘Filmic Identities in the Age of Deep-Fakes’. The media and governments refer to a deep-fake problem, that being the erosion of truth and democracy. And while deep-fakes could pose a range of epistemic and other threats to the public interest, the data has suggested a wider socio-cultural problem.

“Of all the deep-fakes generated in the study’s period, 96 per cent were non-consensual pornography of women. But instead of focusing on the ways deep-fakes might replicate dominant hegemonies – in this case, patriarchy – the broader problem of truth and democracy is foregrounded. So the political answer to the deep-fake problem has been to develop systems to automate the algorithmic detection of deep-fakes and ban their distribution, rather than thinking about how deep-fakes are the product of socio-political and technological assemblages.

“Our project emerged out of this context. We sought to show how creative practice could reveal how ways of perceiving and depicting the gendered body on screen continued between film and effects. We considered how deep-fakes could challenge ways of looking at bodies on screen through the concept of ‘the fit’. By encouraging users to participate with the deep-fake technology, we looked at the ‘good fit’, or the ‘problematic fit’ that would arise when seeing one’s own face deep-faked into another on screen. By cycling through such different versions, we wanted to show that there was creative potential for deep-fakes to challenge assumptions and reveal its relationships to race, class and gender that get perpetuated in popular visual culture, which are then perpetuated in training datasets used for machine learning.”

Concluding by summarising the findings of this deep-fake research, Monin said: “It led us to think about how design and creative practitioners can make sure their voices are heard with the same weight in all kinds of deliberations about AI, but also that they do not simply really reiterate problematic approaches from elsewhere. We need to develop critical technical practices.

“Like other speakers at this Symposium, we also call for universities to be a space for fostering cross-disciplinary collaboration, and not siloing technical advancements within AI to the realms of data and computer science, or confining critical views to the humanities. In our practice, we have found that collaborating across these differences has not always been easy to do. But we argue that it is necessary work for enriching how we practice and examine AI and machine learning technologies.”

Summary by Emma Clancy.